Two Projects. Same Deadlines. One Failure.

What execution stability really means — and why KPIs didn’t see it

At first glance, there was no reason for concern.

Two engineering projects.

Same scope.

Same deadlines.

Same phase durations.

Same reporting.

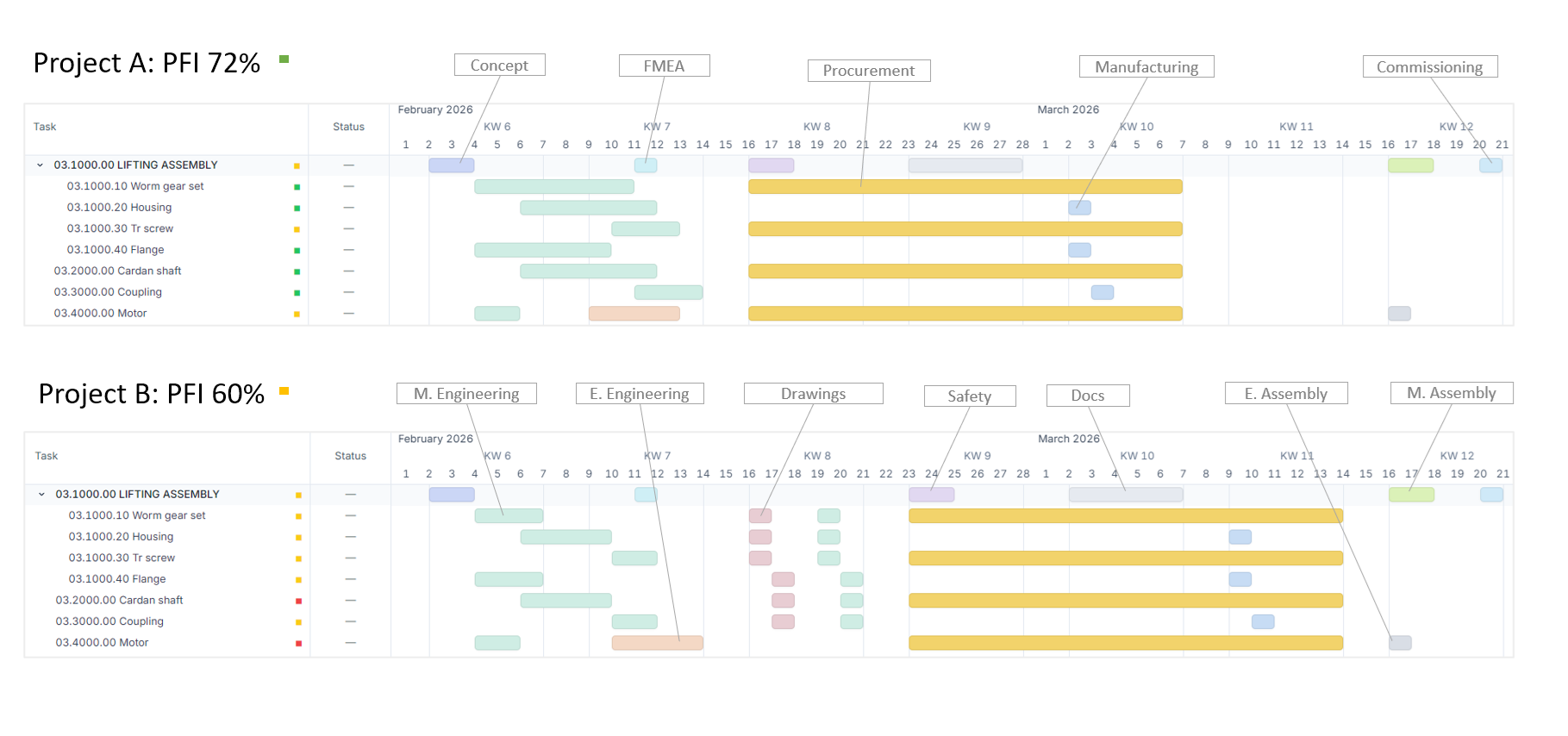

Only the gap-status colors were different.

According to the plan, both projects were “on track.”

And yet, only one of them reached the finish line without strain.

Both projects were defined under identical baseline conditions:

the same overall project duration and the same planned duration of individual phases.

The difference lay deeper —

in how execution was structured.

In Project B, drawings were produced by dedicated drafters.

Engineers focused on 3D; 2D documentation was a separate, formally scheduled phase.

This decision was not accidental.

It was planned, coordinated, and seemed perfectly reasonable.

After all — you can save on salary costs, right?

In Project A, engineers handled both 3D models and 2D drawings themselves.

Not because it was “cheaper.”

And not because it was “simpler.”

But because execution needed to remain flexible.

At the time, this felt like a minor detail.

Almost cosmetic.

It wasn’t.

The problem didn’t start with a mistake.

Not with negligence.

Not with poor performance.

It started with a painfully familiar event:

a delay in the delivery of purchased components.

Nothing extraordinary.

Nothing unexpected.

And this is where the two projects diverged.

In Project B, the delay immediately propagated through the execution chain.

Assembly was blocked, waiting for parts.

So was the customer.

Even with perfect planning, this kind of role separation sharply reduces flexibility

as soon as upstream uncertainty appears.

What a surprise — components arrive later than planned.

There was no buffer.

No structural slack.

Any deviation meant a deadline slip.

The plan was correct.

The execution structure was fragile.

In Project A, something different happened.

The same delay.

The same uncertainty.

But execution did not “break.”

After procurement, a small time buffer had been deliberately built into the flow.

Not as “extra time,” but as room to adapt.

Engineers could afford to “get sick.”

Minor design changes did not trigger cascades of approvals.

Execution bent — but did not collapse.

And when the components eventually arrived on schedule,

that same buffer could be used proactively.

The result?

Project A was completed and delivered to the customer

about one week earlier than planned.

Not through firefighting.

But through stability.

5% of revenue on, say, €5 million.

That’s €250,000 per year.

Now look at the staffing.

Project B

2 drafters at €45,000 = €90,000

2 engineers at €60,000 = €120,000

Total: €210,000

Project A

3 engineers at €70,000 = €210,000

Result?

€0 saved.

€250,000 lost — every year.

It’s worth understanding when a role is economically justified,

before cutting headcount in response to — what a surprise — “economic pressure.”

From a KPI perspective, both projects looked identical — until the very end.

Deadlines.

Budgets.

Completion percentages.

The difference was not in the numbers.

It was in the structure of execution over time.

One project had execution stability.

The other had excellent personnel cost efficiency.

By the time KPIs would have turned red,

the outcome was already decided.

This is where a common mistake appears.

When projects fail, the instinctive reaction is to add time, increase buffers, tighten control.

But time is almost never the root cause.

Let’s review the fundamentals.

The key question is not how much time is available,

but how work is distributed, connected, and able to adapt

when reality deviates from the plan.

Execution stability is a structural property.

And structural problems cannot be fixed with status reports.

Product Flow didn’t appear by accident.

Not as yet another project management tool.

And not as a replacement for ERP or PLM.

But as an Engineering Execution System (EES) —

a layer that makes execution structure visible

where risk actually forms:

at the level of tasks, components, assemblies, and their temporal relationships.

(Not to be confused with MES — Manufacturing Execution Systems.)

Instead of asking:

“Are we still on schedule?”

Product Flow enables a different question:

“How stable is execution right now?”

By analyzing gaps, overlaps, and task flow density,

Product Flow reveals risk before it shows up in deadlines or budgets.

That is what PFI (Project Flow Index) measures.

Not productivity.

Not efficiency.

But a project’s ability to absorb change.

The takeaway is not “don’t use drafters.”

And it’s not “do everything yourself.”

The real difference is this:

One project could adapt without breaking its execution structure.

The other could not.

Same deadlines.

Different stability.

Different outcome.

Projects rarely fail because the plan was wrong.

They fail because execution stability was never considered.

Deadlines fail late.

Execution stability fails early.

And if you see that early enough,

the story can still be rewritten.

This article was originally published on Medium.

You can read the original version here.